Jay Lynn (formerly Ramiro) Gomez in conversation with Ren Weschler

Ramiro Gomez was born in 1986 in San Bernardino, California, to undocumented Mexican immigrant parents—his father a trucker, his mother a janitor at his own school—and displayed artistic talents early on which presently won him admission to CalArts. But he left that institute within a year and instead secured employment as a nanny for an entertainment industry family in the Hollywood Hills (“a part of town,” as he says, “which is largely Latino by day but which, come five in the evening, when the trucks descend and the limos return, reverts to its largely Anglo basis”). Still, his artistic proclivities were hardly dimmed. He began by taking back-issues of architecture, fashion, and design magazines out of the recycling bin, squirreling them back to his room, and subtly doctoring the glossy high-life ads and features by painting in images of the low-income nannies, housecleaners, gardeners, and others who made such life possible. He went on to raid the trash bins at electronics stores for their discarded cardboard boxes, which he in turn fashioned into life-sized painted cut-out flats portraying the sorts of workers whose work goes largely unnoticed, and then subversively leaning such cut-outs against hedges and sites all around town. After which, quitting his nanny job and securing a small studio, he began producing sly pastiches of iconic David Hockney paintings, uncannily reversing their class polarities.

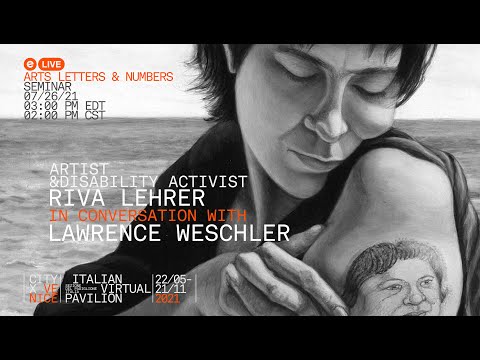

Around this time, in 2016, Weschler profiled the young artist for a full-color Abrams monograph, Domestic Scenes, since which Gomez’s work has gone from strength to strength, getting acquired by major collectors and museums alike, albeit invoking and provoking all sorts of confoundingly paradoxical issues along the way. The sorts of long occluded issues, indeed, that veritably cry out for exploration in the context of a high-end Architecture Biennale.

Over the last few years, Gomez has been traversing a gender transition, and Weschler and she may conclude by exploring some of the issues involved there as well, how they in turn may have been foreshadowed in some of the artist’s earlier work, and what they may portend for the future.

This conversation is part of the series “Mr. Weschler’s Cabinet of Wonders,” as part of “SunShip: The Arc That Makes The Flood Possible,” Arts Letters & Numbers’ exhibition in the CITYX Venice Italian Virtual Pavilion of the 17th Venice Architecture Biennale.